Requirements Viewpoint

Requirements are an over-arching topic for SPES architectural models. Requirements – at different levels of precision – link the needs of stakeholders and the obligations arising from the development context with the architectural elements of the functional, logical, and technical viewpoints.

In this documentation section, we first describe the general approach to the handling of requirements in SpesML, and then describe the modeling elements - first requirements, then tracing relations - used to represent this approach in SpesML modeling. Finally, we give some methodological advice on requirements modeling in SpesML.

General Concept

It is common to differentiate requirements according on the aspects they address. In SpesML we roughly distinguish between:

- Capability requirements, concerning stakeholders’ demands for the system to be able to perform a certain functionality.

- Functional requirements, concerning the input/output behavior of functions and components.

- Quality requirements, concerning software and product quality characteristics such as the well-known “ilities”.

- Constraints, concerning side conditions to be observed during development.

As detailed in the next section, some of these categories can be further refined - for instance, there are different kinds of constraints, depending on whether it is a physical entity to be constrained (e.g., its weight), architectural design decisions (e.g., notational conventions), or the development process (e.g., the need to for certain analyses or tests).

In contrast with the elements of the functional, logical or technical viewpoints, requirements as such are not given a formal semantics. in SpesML. One reason is that for most categories, the Universal Interface Model - on which the formalization of the other viewpoints is based - is not a suitable mathematical basis. The second reason is that even for functional requirements, where such a formalization is intuitively possible, formalized requirements have little use in SpesML. Instead, the system functions of the functional viewpoint can be seen as formalized behavior descriptions of a group of related functional requirements. In practice, this gives a better understanding of the intended functionality than isolated partial behavior specifications.

Requirements are connected to architectural elements or to other requirements through various tracing relations, again addressing different aspects, for instance, whether an architectural element is intended to satisfy a requirement or whether a requirement is derived from another requirement.

Although requirements themselves in SpesML have, for the reasons discussed above, no mathematical semantics in the underlying Universal Interface Model, it is still possible to derive methodically useful properties at the level of the traceability graph consisting of linked requirements and architectural elements. For instance, it is possible to discover unimplemented stakeholder requirements or unmotivated derived requirements; it is also possible to construct lists of verification obligations arising from the graph structure.

Modeling Elements

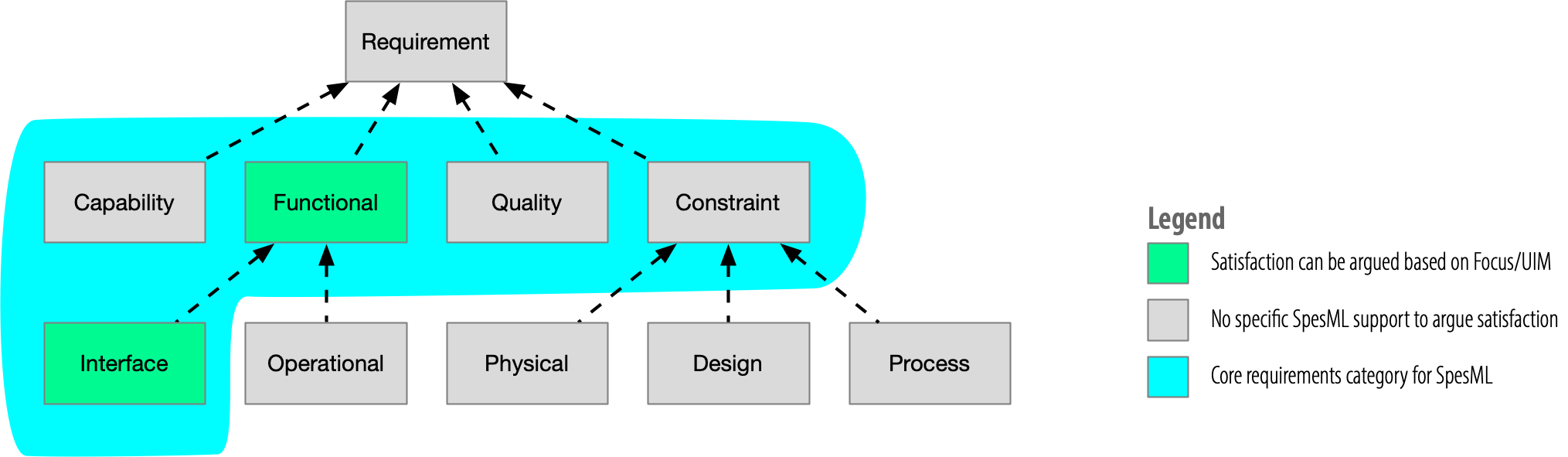

As discussed above, SpesML has different requirements categories aiming at different engineering aspects. These categories are also encoded in the SpesML plugin, so that they can be used for e.g. automated consistency checks. The SpesML requirements taxonomy is shown in the figure below:

The following table summarizes the categories:

| Name | Description | Assignable Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | No specific interpretation, catch-all type and root of other requirements classes. | Any architectural model element |

| Capability | Capability requirements describe functions and operations needed by users or other stakeholders. | Function in FVP, system/components in LVP/TVP. |

| Functional | Requirement that specifies an operation or behavior that a system, or part of a system, must perform. | Function in FVP, system/components in LVP/TVP. |

| Interface | Interaction over interfaces (e.g. protocols, timing, value interdependencies, invariants). | Ports or interfaces, modes or mode diagrams in FVP. |

| Operational | Expected behavior of human actors, e.g. as input for testing and simulation, possibly also for user manuals. | Human actors in context of FVP/LVP |

| Quality | Catch-all category for quality requirements (as in ISO 25010); except perhaps functional correctness and performance (for which we have dedicated categories), these aspects are not further in the scope of SpesML. | Any architectural model element |

| Constraint | Requirement that specifies a constraint on the architecture or the implementation of the system or a system part. | Any architectural model element |

| Design constraint | Requirements that specificies a constraint on the architecture model or the specification of system or of a system part. Design constraints can prescribe certain design patterns (such as the choice of a safety mechanism), they can also be used to describe the rationale behind architectural design decisions. | Any architectural model element |

| Physical constraint | Requirement that specifies physical characteristics and/or physical constraints of the system or of a system part, such as weight, size or resource restrictions or the demand to realize a system part through a certain off-the-shelf component. | Any architectural model element in LVP/TVP. |

| Process constraint | Demands of compliance to process norms or requirements on application of development steps or methods, e.g. particular analyses | Any architectural model element |

The requirements taxonomy might seem a bit overwhelming at first. Indeed, for systems with limited size and complexity it is reasonable to just use the generic “requirement” category. More complex situations benefit from the higher expressibility and the stronger wellformedness conditions gained when differentiating categories.

Requirements Attributes

Each requirement has a set of attributes, capturing the requirement statement itself, as well as some meta-information:

| Identifier | Unique identifier | Core |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Readable name of the requirement, serves as an abstraction of the full requirments text. | x |

| Identifier | Unique identifier of the requirement | |

| Category | Requirements category (see above). | x |

| Text | Requirements content (see next section). | x |

| Status | Degree of maturity and validity of the requirement; for example proposed, accepted, reviewed, implemented, verified. See below for more details on this attribute and validity of requirements. | x |

| Rationale | Explanation of the need of the requirement; this in particular of interest if a requirement does not directly or indirectly originate from a stakeholder, but from a process activity (e.g., a safety analysis) or from an architectural decision. | x |

| States and modes | The state or mode of the system to which the requirement applies. Some systems have various states and modes, each having a different set of requirements that apply to the specific state or mode. | |

| Verification method | How to demonstrate that the requirement holds - e.g., analysis, inspection, description of test method and test case derivation/partitioning, reference to external authorities, … | |

| Source | Origin of the requirement, e.g. a stakeholder or a normative document. | x |

| ASIL | For automotive systems, the Automotive Safety Integrity Level. Similar attributes are relevant for other domains, such as Safety Integrity Level or Design Assurance Level. In addition similar attributes may be needed to capture security requirements (Cybersecurity Assurance Level) or other kinds of criticality, e.g. business or legal risks. |

The attributes marked as core attributes are included in to the SpesML plugin.

The other attributes are optional and may be added to the plugin for specific organizations. Also, the information stored in the attributes may be organization-specific.

Note that we treat safety (represented here through the “ASIL” attribute) not as a requirements category, but rather as additional, orthogonal, attributes. This allows easy extension for, say, security, environmental or legal requirements, and offers more flexibility when it is not a priory clear whether there will not be any overlap between e.g. safety and security, or security and legal requirements.

Requirements Representation

While requirements are essentially just textual objects (stored in the requirements attribute “text”, see the table in the previous section), the representation may be more restricted than natural language alone. In increasing degree of formality, one might envision:

-

Free-form natural language descriptions. However, even for free-from natural language, it is recommended to follow a style guide, such as the INCOSE recommendations [^incose-requirements].

-

Constrained content. For requirements allocated to, for instance, a part of an IBD, it is desirable that the requirement references and constrains phenomena in the scope of the model element it is allocated to, such as ports or internal state variables. In most cases, this will imply a review obligation.

-

Sentence templates, for instance in the style of EARS1 or the Sophist Group’s requirements boilerplates.

-

Formal representations, for instance in the property specification language which is being looked into in a separate project activity, or as formulas in a temporal logic. Formal representations typically are required to be constrained in the sense of Item 2 of this list, in order to ensure that architectural model and property specification are consistent.

Clearly, the more formal the representation, the higher the potential for automated consistency and correctness checks. While within the SpesML project there are no plans to deeply integrate such checks, they are an obvious extension point for further work.

Tracing

Requirements are not isolated model elements, but are typically related to other requirements and other model elements through tracing relationships. The following table lists the tracing relationships used in SpesML. The right-most column (“Tracing”) shows the model elements connected by the requirement (“source/destination”):

- Req: Requirements

- Arch: Main architectural elements of the views, i.e., functions in the functional view or components in the logical or technical views.

- Any: Either requirements or main architectural elements.

| Relationship | Description | Tracing |

|---|---|---|

| Containment | Decomposition into sub-requirements. This is not really a tracing relationship, but instead part of the requirements meta model. It is frequently used for the co-evolution of architecture and requirements (see below). | Req/Req |

| Derive | Derivation of one or more requirements from a source requirement. This is related to the concept of refinement in Focus. | Req/Req |

| Satisfy | Relate requirement with architectural model elements that are intended to satisfy the requirement. | Arch/Req |

| Trace | General-purpose relationship between a requirement and any other model element. The semantics of trace include no real constraints and therefore are quite weak. | Any/Req |

| Verify | Relate requirements with test or simulation scenarios or other model elements. | Any/Req |

| Require | Needed for A/C-like arguments. An architectural model element can require requirement to make explicit assumptions needed to satisfy other requirements. | Arch/Req |

| Matches | In order to link assumptions of one model element with guarantees of another. Semantically, the Matches relation is identical to Derive; the difference is purely methodological. | Req/Req |

The most frequently used relationships are Satisfy and Derive. The Satisfy relationship is used to state that an architectural element should satisfy a requirement. Thus, a Satisfy relationship gives rise to the verification obligation of checking whether this in indeed the case. There are multiple ways to discharge such an obligation; in industry, functional requirements are typically verified by tests and constraints are verified by reviews. In some development process descriptions, the Satisfy relation is referred to as an allocation of requirements to architectural elements.

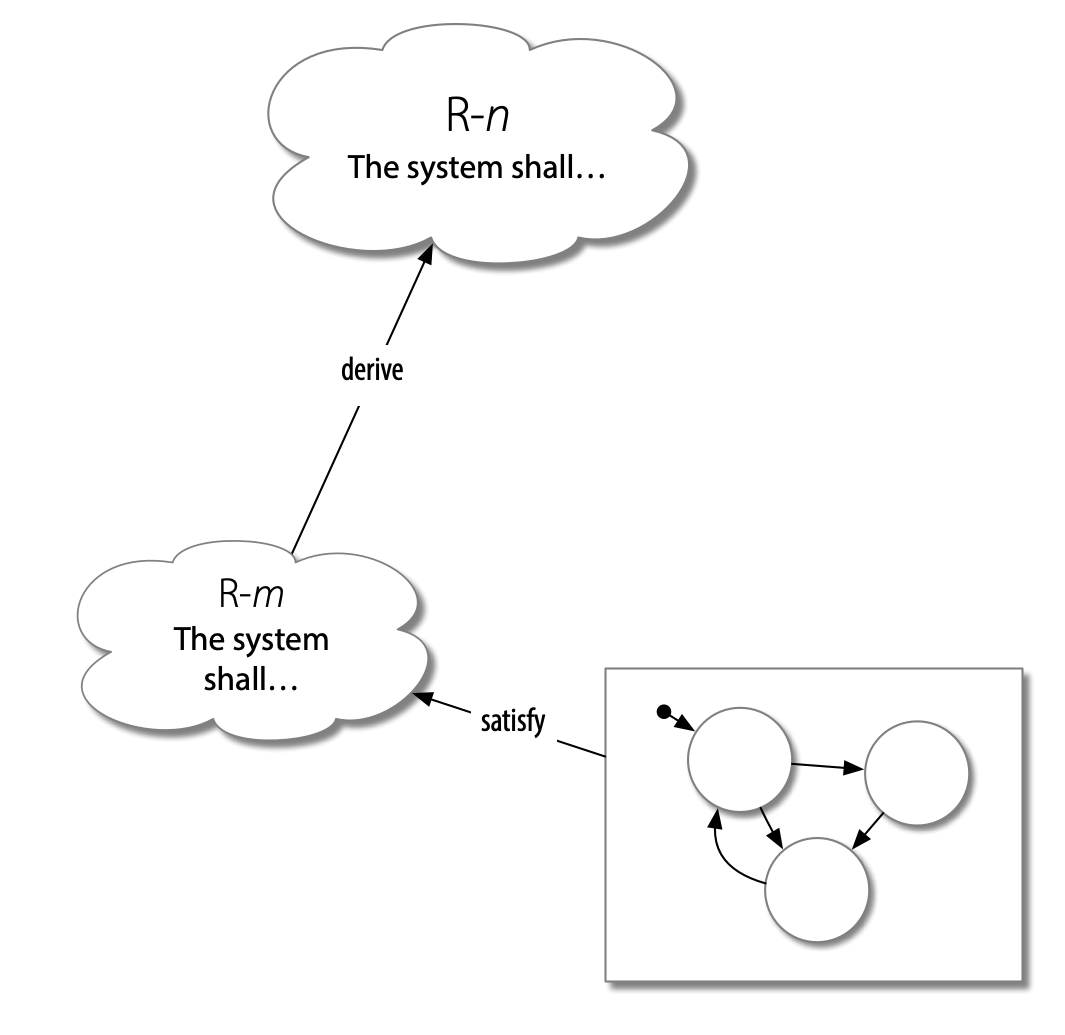

The Derive relationship is used to add detail or to include certain design decisions. In the absence of formal requirements notations, derive does not have a formal semantics, but intuitively, if a requirement R-m is derived from a requirements R-n, we would expect that when R-m is valid for a given system, then so is R-n (note that this is a more liberal demand than the universal “R-m implies R-n”). Since in general it is not possible to automatically verify this expectation, the Derive relationship gives rise to a verification obligation that needs to be discharged during development (typically through a review).

It is a common pattern that an architectural element satisfies a requirement, which itself is derived from a more high-level requirement:

Of course, there may be a longer chain of derived requirements, up to an initial stakeholder requirement.

Requirements Fulfillment

Above we have seen that SpesML requirements have an attribute for requirements status information. It is good practice to be able to represent the two-level verification obligation typically needed for requirements:

- Review of requirements: Do we accept the requirement and agree with it? This obligation is quite straightforward and easily supported through requirements quality criteria such as those of INCOSE [^incose-requirments].

- Verification of the system against requirements: Does the system - or a part of the system - fulfill the requirement? Note that this is related to the use of Satisfy links. The remaining question is thus, whether indeed the architectural element at the source of the link indeed fulfills the requirement at the end of the Satisfy link.

An immediate question when considering Satisfy links and validity of requirements is whether the source of the Satisfy link stems from the (real) system to be developed or from the model of the system to be developed.

For SysML, the interpretation is that it is the real system - or a part of the real system - that has to satisfy the requirement. Typically, requirements satisfaction is demonstrated through tests. Consequently, in SysML, Verifies links are used to link test cases with requirements.

For SpesML, the situation is slightly different. Testing of systems is highly dependent on the nature of the (real) system as well as on test environments, test techniques and test tools. Thus, testing of systems is out of scope of the SpesML project with its focus on architectural models.

On the other hand, there are verification goals that can be fulfilled considering architectural models only:

- Design constraints, which pose demands on the architectural model, are obviously to be verified on the model itself.

- In systems engineering, simulation of an architectural model with executable components behavior specifications is a specific form of prototyping to get early feedback on the feasibility of the chosen architecture to satisfy requirements.

Approaches to Requirements Fulfillment

Given the preliminaries of the previous sections, the next step is to consider combinations of either model or real system and requirements category, and to determine

| Category | Description | Fulfillment for Model | Fulfillment for System | Note | Impact on SpesML |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Describes functions and operations needed by users. | Demonstrate through simulation | Demonstrate through test | Capability requirements (“the system shall be able to…”) are typically existential properties. Hence non-exhaustive demonstation scenarios are sufficient. | In scope for models; out of scope for system. |

| Functional | Specifies an operation or behavior that a system, or part of a system, must perform. | (Formal) verification, simulation | Test | Functional requirements (“Whenever…”) are typically universal properties. At the model level, formal verification can be used. For simulation or test, we need some coverage argument as a rationale why the chose scenarios are sufficient. | Out of scope for formal verification; in scope for test or simulation of models; out of scope for system. |

| Interface | Value dependencies and invariants | (Formal) verification, simulation | Test | Same as for functional requirements. | Same as for functional requirements. |

| Quality | Mainly ISO 25010-like “ilities” | Various experiments | Various experiments | In practice, quality requirements are often reformulated as sets of physical or design constraints; in some cases also as functional requirements. | Out of scope. |

| Physical constraint | Specifies physical characteristics or limit constraints of the system, or a system part, including resource limits (memory, processing power). | n/a | Measurements and experiments. | Demonstration of physical constraints may be supported in architecture models through some aggregation algorithms or consistency checks. | Out of scope. |

| Design constraint | Specifies a constraint on the architectural model used to represent a a system a system part. | Reviews, inspections and analyses of models | n/a | SpesML has some model analysis support through the well-formedness checker. | Well-formedness rules only. |

| Process constraint | Specify need for compliance to process norms or need to perform certain activities (e.g., risk analyses) | Audits | n/a | Audits examine the chose development approach and the development activities; clearly, there must be some evidence produced during development (an “audit trail”). SpesML models or model annotations may contribute as evidence, but this is not yet well enough understood. | Out of scope. |

In summary, only the fulfillment of requirements of the categories given in the first three rows (capability, functional and interface requirements) are directly in the scope of SpesML. In addition, the fulfillment of certain design constraints - those expressed as well-formedness rules - can be regarded as being in scope.

The fulfillment of requirements of the other categories is not in the scope of the SpesML project. These categories should not be neglected in a systems development project, but questions of their fulfillment are beyond what can reasonably be reached within SpesML.

Representation of Requirements Fulfillment

Common to the capability, functional and interface requirements categories is that their fulfillment is demonstrated primarily through test or simulation. For SpesML, the main question here is whether test simulation/test setups, scenarios and results should be included or referenced in the architectural models. For functional and interface requirements - typically being universal properties -, in addition a coverage argument may need to be documented.

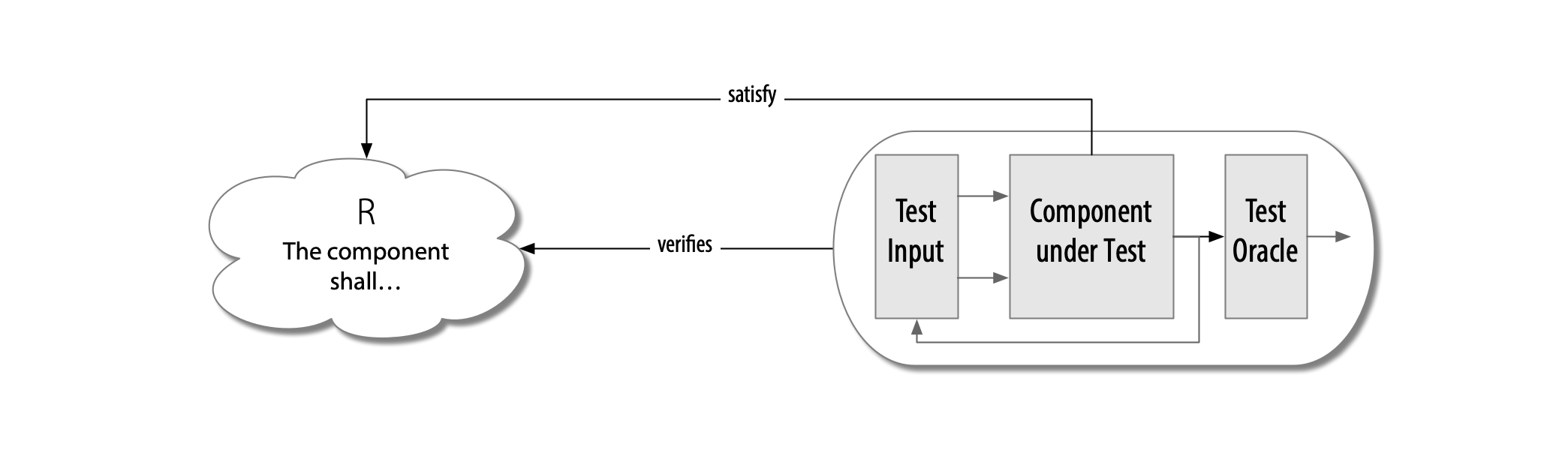

The Verify-relationship is the main relationship to demonstrate fulfillment of requirements. It can be used to to link requirements to test or simulation information that is used to verify this requirement. Fulfillment also needs to consider which system or model element is responsible for ensuring a requirement; this aspect is denoted by the Satisfy relationship.

In summary, the assertion that

- a component (or a system or white-box function of the functional view) satisfies a requirement R, and that

- this fact is demonstrated through a test setup

is modeled with Verify and Satisfy links as shown in this figure:

Automated Requirements Status Updates

Since through the setup described above requirements fulfillment can be demonstrated by executing a test setup, it seems natural to use the result of the execution (from the test oracle) to automatically update the status attribute of the requirement.

However, in SpesML this functionality is not implemented. The reason is that when the model is changed (either the requirement, the test object or the test setup), the test setup needs to be run again. This is a special case of automated change management, which is not implemented within SpesML.

Modeling Guidelines

As in most professional activities, for system development, certain activities are recurring and can be abstracted into “patterns”. This section gives a small selection of examples.

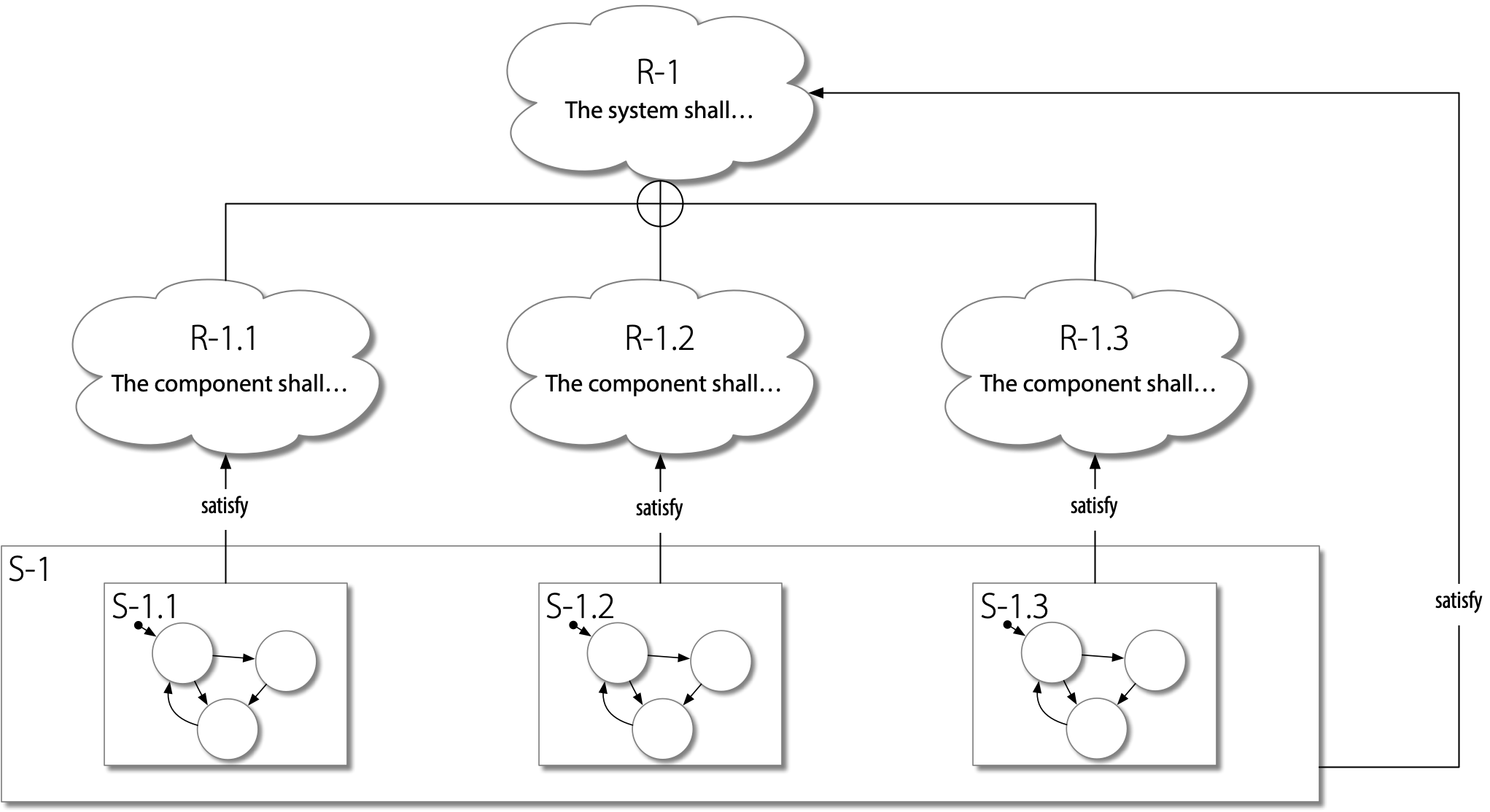

Co-Evolution of Requirements and Architecture

Frequently, requirements and architecture co-evolve in the sense that not only are architectural decisions based on requirements, but also that vice versa requirements decomposition and derivation may depend on architecture. This “zigzagging” between requirements and architecture is also recognized by development standards (see, for instance, ISO 26262 2, Part 10, Clause 7).

It can be represented in SpesML through the common decomposition of requirements and architecture, as shown in the figure below:

Note that requirements are decomposed through the Containment relationship, which is not not a proper trace relation. Instead, containment is encoded into the requirements model itself. It is used to divide a requirements into sub-requirements which can then be traced, allocated and verified independently.

When using this co-evolution pattern, one would expect the following consistency conditions to hold:

-

Taken together, the sub-requirements must imply the parent requirement.

-

If the parent requirement is satisfied by a function (in the sense of an architectural element) F or by a logical or a technical component E, the sub-requirements must be satisfied by a sub-function of F (in the sense of the functional hierarchy) or by sub-components of E, respectively.

Development Against Assumed Requirements

Subsystem development frequently occurs in parallel with, or earlier than, development of the main system. Typical examples for such concurrent development are:

- Early development of subsystems or components within an organization before requirements are finalized and agreed upon; in fact, in some cases, it is precisely the experience of such early development sub-projects that is needed to finalize requirements and architecture.

- Development of “baukasten” subsystem or components within an organization with the intent of using these elements in the construction of product systems for customers.

- Development of off-the-shelf subsystems or components by suppliers.

In these cases, development happens against assumed requirements, as there are no stable system requirements yet available. This means that it is not certain that the independently developed subsystem or component does indeed fulfill the properties required by the system. Moreover, the same argument goes in the other direction: A subsystem or component can have requirements on the integration context which may or may not be satisfied by the system to be developed.

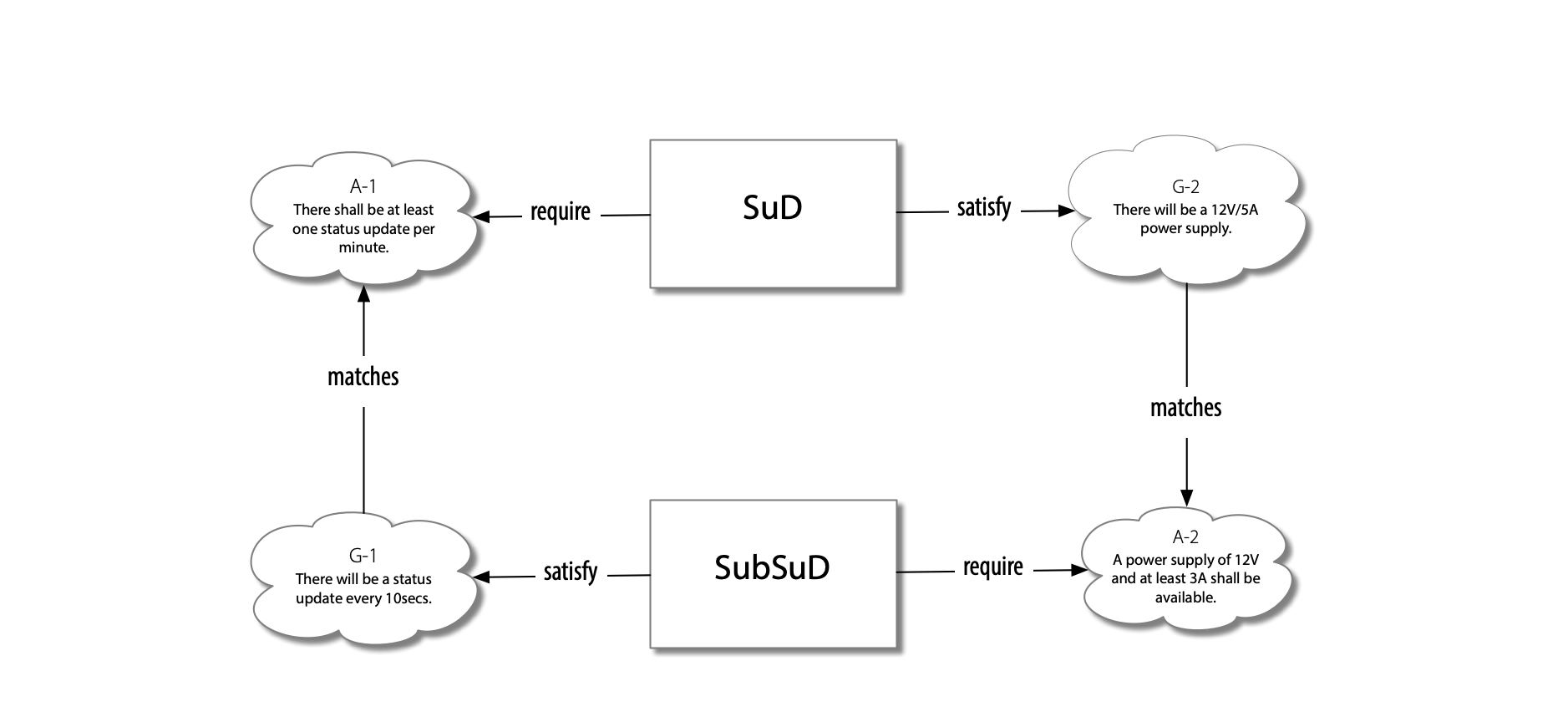

In SpesML, the Require and Matches relationships are intended to represent such development situations:

-

The Require relationship is used to state expectation on the integration context of a subsystem (from the point of view of the subsystem), as well as expectation on the properties to be fulfilled by the subsystem (from the point of view of the system).

-

The Matches relationship is then used to describe which of the properties satisfied by the system imply that the integration demands of the subsystem are fulfilled, as well as which of the properties satisfied by the subsystem imply that the expectations of the system on the subsystem are fulfilled.

As an example, given a supplier intent on developing a subsystem that generates status information. When starting development, it is not yet determined at which frequency, let only with which precise formats and interface technologies and protocols, the status information has to be produced. Still, the supplier continuous working and develops such a system. During development, it turns out that there are some demands on whatever system the subsystem is to be integrated in - most prominently, electrical power with certain characteristics has to be available. Thus, subsystem development proceeds against assumed requirements (which are then guaranteed or satisfied by the subsystem) and also for an assumed integration context (which is required by the subsystem).

Conversely, the system developer discovers a need to have a subsystem to provide status messages with a certain minimum update rate. Clearly, the subsystem will have power demands; hence, a certain power budget is guaranteed by the system.

When integrating the subsystem of our example, the integrator has to ensure that the guaranteed performance of the subsystem -i.e., the frequency of status delivery- matches the demands of the system under development. Conversely, the integrator also has to ensure that the expectations of the subsystem -i.e., its power demands- can be satisfied by the system under development. While in general it is not possible to automatically verify such pairings of assumed (Require) and guaranteed (Satisfy) properties, it is typically feasible to manually review them. The Require/Matches relationships help to identify and track these review obligations:

Note that in general the Require/Matches combinations may be circular: Without supplied power, it should come as not surprise if the subsystem fails to deliver status information. On the other hand, perhaps the system will only route power to the subsystem if the status information implies the subsystem is indeed alive?

Such circles must be broken by rephrasing one of the requirements in a way such that at least one component fulfills its guarantee in advance; only if then its assumed requirements are not fulfilled by the the other component may the first component renege on its guarantees. Clearly, this approach suitable only for behavioral properties. However, in practice this will rarely be a problem. Circularities are unlikely to occur in design constraints, and assumptions related to quality requirements typically involve resource guarantees allocated through a top-down budgeting process.

Note that the Matches relationship is closely related to Derive, in that they state that if the source requirement is valid, the destination requirement of the trace should be valid, too. As with Derive, Matches gives rise to a verification obligation, namely to verify that Required requirements of the subsystem are indeed fulfilled by Satisfied requirements of the main system, and vice versa.

Incremental Clarification of Requirements

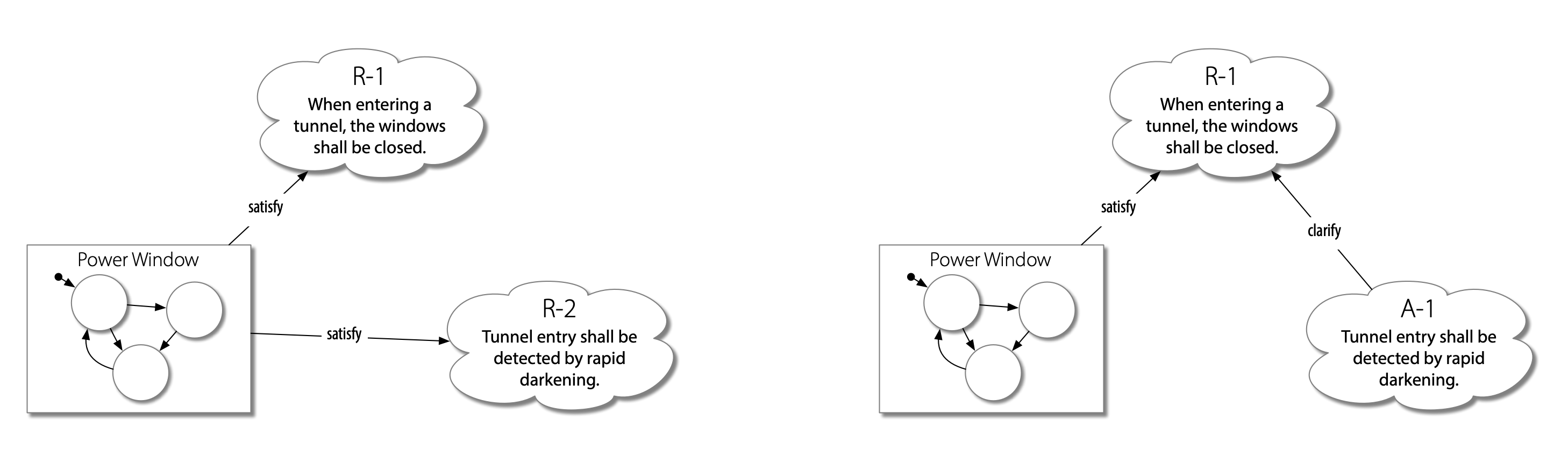

It is to be expected that in many cases it is not clear how a certain situation should be modeled. For instance, in the power window system case study, window operation is triggered not only by the driver and passengers, but also by light sensors. The intent here is that windows should be closed when entering a tunnel, in order to keep the stale air in the tunnel from polluting the car.

The obvious way to model this situation is as in the left side of the following figure: There are initial requirements that not only state that the window should close when entering a tunnel, but also the intended means of detecting tunnel entry (an alternative would be for instance a location-based approach). An alternative, if we believe the decision on tunnel detection should be done by the system designers, we might document this decision as a clarification (right side of the figure):

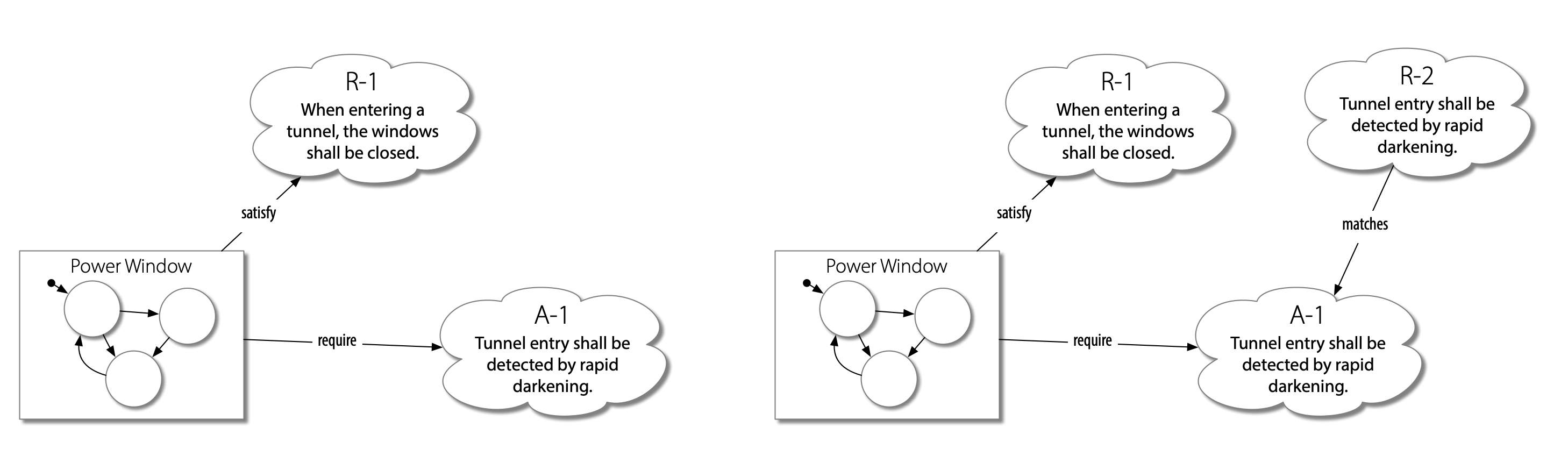

It might be preferable, however, to emphasize this decision in order to enforce alignment with customers and other stakeholders; in this case, one might model the tunnel detection decision as an assumption (left side), which is kept dangling until validated by finally matching to a stakeholder requirement (right half):

Note that at first blush this use of the Require and Matches relationships seems to be quite different from the use for concurrent development of system and subsystem development as outlined above. Its essence, however, is the same: We discover a requirements gap and solve it by developing against an assumed requirement.

Derived requirements

The co-evolution is not restricted to the structure of requirements and architecture. For instance, new requirements may arise due to safety analyses, necessitating additional functionality to mitigate newly discovered failure modes. Another reason for the introduction of new requirements may be architectural decisions that necessitate clarification of intended behavior beyond what can be inferred from stakeholder-derived requirements. In DO-178C 3, such requirements are referred to as “derived requirements”.

Methodologically, there are different ways to represent such derived requirements in SpesML:

- One approach is to represent derived requirements as assumed (required) requirements. This is related to the power window example above. The main advantage of this approach is that it is obvious that these requirements need to be clarified with stakeholders: A stakeholder requirement justifying the decision has to be introduced and matched with the assumed requirement.

- Alternatively, derived requirements can be introduced and linked to architectural elements (via Satisfy-traces) analogously to stakeholder-derived requirements. Since they are not traceable to a stakeholder requirement, however, in any case a rationale should be documented in the requirement and the source attribute of the requirement should state that this is a derived requirement. This approach is preferable for requirements justifying or constraining architectural decisions that do not need to be aligned with stakeholders. Typically, such aspects are modeled as design constraint requirements.

References

-

A. Mavin, P. Wilkinson, A. Harwood and M. Novak, EARS (Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax). In: 17th IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference, 2009, pp. 317–322. ↩

-

ISO, ISO 26262, 2018. ↩

-

RTCA, DO-178C - Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification, 2011. ↩